By Andrea E. Stumpf

International partnership programs are a favorite type of structured partnership in the international arena. These partnership programs are found all over the international community, particularly in international development, and have become venues of choice for many international partners seeking to join forces and leverage resources to meet global and local needs. Over the past decades, international partnership programs have evolved into major north-south income transfer instruments. They are crucial to meeting the world’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030.

But what are they? We can start by saying what they’re not. Let’s contrast the private sector, where the baseline is corporate. The starting point is the legal entity, the structure is incorporated, and the context is statutory. You can partner up, but you either partner within the legal entity construct or among legal entities, each within their own constructs. A lot is predefined and prescribed, like statutory duties of board members, tax and disclosure regulations, liability jurisprudence, and more.

There is, however, another world out there. Like all those who get to know their own country better by traveling abroad, a diversion into the international arena can be instructive. It’s like moving from terra firma to the high seas, or breaking through the thermosphere into space, to exaggerate just a bit. Much of the international arena operates on unincorporated grounds. The laws applicable to an international (i.e., multilateral, intergovernmental) entity are the entity’s own “laws,” often referred to as the “rules of the organization” – meaning its articles of agreement, policies, procedures, etc. – as defined by its members (i.e., member states). As you can imagine, that leaves plenty of room for creativity and malleability, both within each entity and in how those entities partner with others.

So back to our subject. Many of these international partnerships take their shape as international partnership programs – melding partners and programs in a more or less branded platforms. While an international partnership program is an identifiable arrangement, it is not a separate entity, nor is it fully embedded in an existing entity. It is a hybrid, on the one hand positioning a new, dedicated partnership body that relates to the shared program, but on the other hand receiving support from an existing entity, typically an international organization, like the World Bank. As an international supporting entity, the World Bank is a multilateral development bank and one of the Bretton Woods institutions that emerged after World War II. The Bretton Woods sisters and their progeny were created sui generis by agreement rather than statute, internationally rather than domestically. While much has been written about how these and other international organizations – like United Nations agencies and many others – are organized, little has been written about how these organizations organize their partnerships. With few external parameters, this can be an amazingly open space to engage.

With great variety, many of these partnership programs seek to promote global public goods, like responses to climate change and refugee flows, or get rid of global public bads, like ebola and other diseases. Many are set up to pursue the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the international community as targets for 2030 (following the precursor Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) through 2015), which cover poverty, health, education, equality, food, water, energy, peace, partnerships and much more. Examples abound, but I will mention a few international partnership programs I currently support: the Famine Action Mechanism to strengthen the humanitarian-development nexus for zero tolerance of famine, the Global Financing Facility to improve health and nutrition for women, children and adolescents, the Global Concessional Financing Facility to support refugees and their host communities in middle income countries, and the newly emerging Energy Storage Partnership to direct innovation to developing country energy needs. International partnership programs populate the development landscape at global, regional and country levels.

In establishing international partnership programs, the choice of partner tends to be functional. Most partners have specific roles. Supporting entities often lead the creation of these platforms, while offering administrative (secretariat) and fiduciary (trustee) support, often including implementation support. Donors contribute funds, while beneficiaries – usually developing country governments receiving official development assistance (ODA) – contribute their voice and implementation. Other stakeholders like non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) round out the mix to weigh in for greater buy-in. Overall, everyone shares their perspectives and priorities, experience and expertise in what is ideally a consensus-based setting.

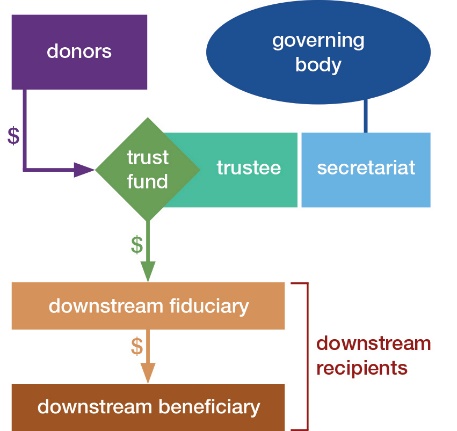

Here is a sample scenario: A sponsoring team at a supporting entity says “we want to rally the international community to create an international partnership – with donors paying into a trust fund, an inclusive governing body supported by a secretariat, and coordinated, supervised funding streams that finance the partnership’s activities,” and they get to structuring, designing and drafting in collaboration with their like-minded partners. A useful option in this structuring exercise is to lean on this existing international organization as the supporting entity to establish and manage the trust fund, house the secretariat, appraise and supervise the funded activities, and generally hold the thing together as a partnership – brand name, website, and all – while drawing partners into the collective.

Classic form of an international partnership program

To be sure, this is not a structuring free-for-all. The “rules of the organization” of the supporting entity do a lot to define the operations of the partnership. The donors and recipients – typically sovereigns and their ministries or agencies – each bring their domestic rules and requirements. But even as these factors become baselines for the partnership umbrella, the latitude for structuring and the leeway in design choices can still be significant.

Ultimately, unincorporated international partnerships are like alliances, established on their own agreed terms, partnerships through and through. Even when an international partnership looks and feels like an organization, with billions of dollars flowing through, its legal entity status rests within each of the partners relative to their allocated roles and responsibilities. Even the supporting entity is typically positioned as a partner more than a service provider. This unincorporated setting also offers significant advantages for international partners to operate effectively. Here are three:

- No Divided Loyalties. When international partners convene in a governing body supported by an existing international organization, there is no distinct partnership legal entity to which that body has a fiduciary relationship. This means there is no direct responsibility or liability in the way a board would have to its corporation and shareholders. Instead, the fiduciary roles in the international partnership are disseminated elsewhere – for example to the trustee or other downstream fiduciaries. This frees the governing body members to come as themselves and represent their own institutions, rather than be positioned as representatives in their personal capacities with fiduciary duties to the whole. Appearing as domestic or international civil servants from governments or multilaterals, representatives can stay loyal to their respective home organizations – something they are usually supposed to do – without conflicting duties to the partnership per se. If, for example, a donor decides to withhold funds or approval for additional projects, it does not matter if that undermines the “business” of the partnership program; the donor can make its decision for any reason whatsoever, based entirely on its own views and requirements.

International partnerships consist of both entities and people as partners.

- As-agreed Fiduciaries. A central tenet of international partnerships that include fund flows is the negotiated nature of “trusteeship.” Usually the international fiduciary performs only as articulated in the relevant fund flow agreements, with the express disavowal of any domestic notions of trusts and trustees – performing within the four corners of the agreements, as it were. This lets the supporting entity acting as trustee – or more blandly, as administrator – stay true to its own internal policies and procedures. This also lets partners establish their risk profiles by choosing to rely on more or less robust fiduciary frameworks, including environmental and social safeguards, supervision, and reporting mechanisms. A good deal can also remain unarticulated, particularly with respect to recourse and remedies (see the next point), by placing reliance more on relationships and track records than on indemnifications and litigation. International trustees can come in different flavors, including “full trustees” that sign up to full responsibility for fund use including supervision of grant recipients, and “limited trustees” that become hands-off by transferring both funds and fiduciary responsibility to the recipients, in each case depending on what the partners negotiate.

- Privileges and Immunities. Whether accorded to sovereigns or their multilateral organizations, a layer of protection typically colors much of what international partnerships do. Operating within the penumbra of privileges and immunities (P&I), the partnership is usually based more on a handshake – reliance on each other’s engagements – than the specter of legal liability. This is particularly important for supporting entities that benefit from “functional immunities” for the organization, staff and archives in the many roles they can play. Although international organization P&I are being challenged on various fronts, as long as they still exert some protective sheen, international partners can afford to disperse responsibilities amicably amongst themselves and hold each other accountable in a partnering kind of way. For example, when funds are misused and donors expect to be refunded, it is not so much because their fund flow agreements have enforceable clauses, but rather because partners have policies, track records and understandings that undergird their expectations.

Needless to say, these features can pose challenges when adding the private sector to international partnerships (not to be confused with project finance-type PPPs). And yet, achievement of the SDGs and other international development objectives, like supporting host communities for refugee flows, are increasingly contingent on catalyzing, coordinating and collaborating with the private sector. The World Bank Group, for example, now refers to the “cascade” – crowding and leveraging in the private sector before following with international funds, thereby layering and reinforcing the support from private to public, as available and needed.

How to handle conflicts of interest in these public-private partnerships can be a big issue. On the one hand, how can we add private sector contributions to international trust funds without skewing the competitive playing field and playing into conflicts of interest? On the other hand, how can we bring international players into corporate settings without compromising their duties of institutional loyalty or undermining their own mandates? The answer is surely not to be strict constructionists and preclude partnering altogether. Instead, there is room to widen the lens: to see synergies in addition to conflicts of interest (I call these synergistic conflicts); to recognize and shape trade-offs; to open up the discussion, opt for transparency and awareness, and disclose and manage where possible.

In many ways, the optimal structure and design of international public-private partnerships remains a frontier for innovation and vision – but a frontier that starts with understanding how international partners create their international partnerships.

© Andrea E. Stumpf 2019